Sitting Bull

| Sitting Bull | |

|---|---|

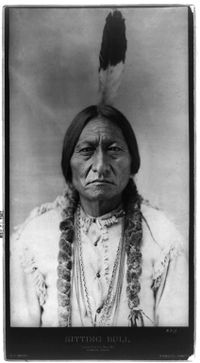

Sitting Bull in 1885

|

|

| Tribe | Hunkpapa |

| Born | c. 1831[1] Grand River, South Dakota |

| Died | December 15, 1890 (aged 59) Grand River, Standing Rock Indian Reservation |

| Native name | Tȟatȟaŋka Iyotȟaŋka (born Hoka Psice) |

| Known for | Battle of Little Big Horn, resistance to USA |

| Cause of death | Shot by Indian Police |

| Resting place | South Dakota |

| Religious beliefs | Lakota |

| Spouse(s) | Light Hair Four Robes Snow-on-Her Seen-by-her-Nation Scarlet Woman |

| Children | One Bull (adopted son) Crow Foot (son) Many Horses (daughter) Walks Looking (daughter) (adopted daughter) |

| Parents | Jumping Bull (father) Her-Holy-Door (mother) |

| Relatives | Big Foot (half brother) White Bull (nephew) |

| Signature

|

|

Sitting Bull (Lakota: Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake (in Standard Lakota Orthography[2]), also nicknamed Slon-he or "Slow"; (c. 1831 – December 15, 1890) was a Hunkpapa Lakota Sioux holy man who led his people as a war chief during years of resistance to United States government policies. Born near the Grand River in Dakota Territory, he was killed by Indian agency police on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation during an attempt to arrest him and prevent him from supporting the Ghost Dance movement.

He is notable in American and Native American history for his role in the major victory at the Battle of the Little Bighorn against Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer and the U.S. 7th Cavalry Regiment on June 25, 1876, where Sitting Bull's premonition of defeating the cavalry became reality. Seven months after the battle, Sitting Bull and his group left the United States to Wood Mountain, Saskatchewan, where he remained until 1881, at which time he surrendered to US forces. A small remnant of his band under Chief Waŋblà Ǧà decided to stay at Wood Mountain. After his return to the United States, he briefly toured as a performer in Buffalo Bill's Wild West show.

After working as a performer, Sitting Bull returned to the Standing Rock Agency in South Dakota. Because of fears that he would use his influence to support the Ghost Dance movement, Indian Service agent James McLaughlin at Fort Yates ordered his arrest. During an ensuing struggle between Sitting Bull's followers and the agency police, Sitting Bull was shot in the side and head by Standing Rock policemen, Lieutenant Bull Head (Tatankapah) and Red Tomahawk Marcelus Chankpidutah, after the police were fired upon by Sitting Bull's supporters. His body was taken to nearby Fort Yates for burial, but in 1953, his remains were possibly exhumed and reburied near Mobridge, South Dakota, by his Lakota family who wanted his body to be nearer to his birthplace. However, some Sioux and historians dispute this claim and believe that any remains that were moved were not those of Sitting Bull.

Contents |

Early life

Sitting Bull was born in a tipi located near the Grand River passing through the Standing Rock Indian Reservation in the Dakota Territory. He was named Slon-He at birth, translated as "Slow" in standard Lakota language. In traditional Lakota fashion, he was given one of his father's names, Tȟatȟaŋka Iyotȟaŋka, translated as "Sitting Bull", due to a leadership role in a battle between the Lakota and Crow people. The event occurred when he was 14 years old, and led a charge and struck before the opposing Crow forces could, resulting in victory for the Lakota people without any fatalities.

Red Cloud's War

Sitting Bull led numerous war parties against Fort Berthold, Fort Stevenson, and Fort Buford and their environs from 1865 through 1868.[3] Although Red Cloud was a leader of the Oglala Sioux, his leadership and attacks against forts in the Powder River Country of Montana were supported by Sitting Bull's guerrilla attacks on emigrant parties and smaller forts throughout the upper Missouri River region.

By early 1868, the U.S. government desired a peaceful settlement to Red Cloud's War. It agreed to Red Cloud's demands that Forts Phil Kearny and C.F. Smith be abandoned. Chief Gall of the Hunkpapas (among other representatives of the Hunkpapas, Blackfeet, and Yankton Sioux) signed a form of the Treaty of Fort Laramie on July 2, 1868 at Fort Rice (near Bismarck, North Dakota).[4] Sitting Bull did not agree to the treaty. He continued his hit-and-run attacks on forts in the upper Missouri area throughout the late 1860s and early 1870s.[5] The events of 1867–1868 mark a historically debated period of Sitting Bull's life. According to historian Stanley Vestal, who conducted interviews with surviving Hunkpapa in 1930, Sitting Bull was made "Supreme Chief of the whole Sioux Nation" at this time. Later historians and ethnologists have refuted this concept of authority, as the Lakota society was decentralised. Lakota bands and their chiefs made individual decisions.

The Great Sioux War of 1876–1877

Sitting Bull's band of Hunkpapas continued to attack migrating parties and forts in the late 1860s. When in 1871 the Northern Pacific Railway conducted a survey for a route across the northern plains directly through Hunkpapa lands, it encountered stiff Sioux resistance.[6] The same railway people returned the following year accompanied by federal troops. The survey party was again attacked by Sitting Bull and the Hunkpapa and was forced to turn back.[7] In 1873, the military accompaniment for the surveyors was considerably larger, but Sitting Bull's forces resisted this survey "most vigorously."[8]

The Panic of 1873 forced the Northern Pacific Railway's backers (such as Jay Cooke) into bankruptcy. This financial condition halted construction of the railroad through Sioux territory. At the same time, other men became interested in the possibility of gold mining in the Black Hills. In 1874, Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer led a military expedition from Fort Abraham Lincoln, near Bismarck, to explore the Black Hills for gold and to determine a suitable location for a military fort in the Hills.[9] Custer's announcement of gold in the Black Hills triggered the Black Hills Gold Rush. Tensions increased between the Sioux and European Americans' seeking to move into the Black Hills.[10]

Although Sitting Bull did not attack Custer's expedition in 1874, the US government was increasingly pressured to open the Black Hills to mining and settlement. It was alarmed at reports of Sioux depredations (encouraged by Sitting Bull). In November 1875, the government ordered all Sioux bands outside the Great Sioux Reservation to move onto the reservation, knowing full well that not all would comply. As of February 1, 1876, the Interior Department certified as "hostile" those bands who continued to live off the reservation.[11] This certification allowed the military to pursue Sitting Bull and Lakota bands.

According to one recent historical commentary, many Lakota bands allied with the Cheyenne during the Plains Wars because they thought the other nation was under attack by the US. According to this theory, the major war should have been called "The Great Cheyenne War". Since 1860, the Northern Cheyenne had led several battles among the Plains Indians. Before 1876, the US Army had destroyed seven Cheyenne camps, more than those of any other nation.[12]

However, other historians like Robert Utley[13] and Jerome Greene[14][15] also using Lakota oral testimony aver that the Lakota coalition of which Sitting Bull was the ostensible head was the primary target of the federal government's pacification campaign.

Battle of the Little Bighorn

It was during the period between 1868–1876 that Sitting Bull developed into the most important of Native American chiefs. After the Laramie Treaty of 1868 and the creation of the Great Sioux Reservation, many traditional Sioux warriors, such as Red Cloud of the Oglala and Spotted Tail of the Brulé, came to reside permanently on the reservations. They were largely dependent for subsistence on the US Indian agencies. Many other chiefs, including members of Sitting Bull's Hunkpapa band such as Gall, at times lived temporarily at the agencies. They needed the supplies at a time when white encroachment and the depletion of buffalo herds reduced their resources and challenged Native American independence.

In 1875 the Northern Cheyenne, Hunkpapa, Oglala, Sans Arc, and Minneconjou camped together for a Sun Dance together, with both the Cheyenne medicine man White Bull or Ice and Sitting Bull in association. This ceremonial alliance preceded their fighting together in 1876.[12] Sitting Bull had a major revelation.

At the climactic moment, "Sitting Bull intoned, 'The Great Spirit has given our enemies to us. We are to destroy them. We do not know who they are. They may be soldiers.' Ice too observed, 'No one then knew who the enemy were – of what tribe.'...They were soon to find out." (Utley 1992: 122–24)

Sitting Bull's refusal to adopt any dependence on the white man meant that at times he and his small band of warriors lived isolated on the Plains. When Native Americans were threatened by the United States, numerous members from various Sioux bands and other tribes, such as the North Cheyenne, came to Sitting Bull's camp. His reputation for "strong medicine" developed as he continued to evade the whites.

After the January 1st ultimatum of 1876, when the United States army began to track down Sioux and others living off the reservation for extermination, Native Americans flocked to Sitting Bull's camp. Sitting Bull took an active role in encouraging this "unity camp". He sent scouts to the reservations to recruit warriors, and told the Hunkpapa to share supplies with those Native Americans who joined them. An example of this generosity is Sitting Bull's taking care of Wooden Leg's Northern Cheyenne tribe. They had been impoverished by Captain Reynold's March 17, 1876 attack and fled to Sitting Bull's camp for safety.[12]

The Hunkpapa chief provided resources to sustain the new recruits. Native Americans were attracted to the camp not only for security but by its generosity. Over the course of the first half of 1876, Sitting Bull's camp continually expanded, as natives joined him for safety in numbers. It was this large camp which Custer found on June 25, 1876. Sitting Bull did not take a direct military role in the ensuing battle; as a head chief, he was charged with defensive responsibilities. His leadership had attracted the warriors and families of the extensive village, estimated at more than 10,000 people.

On June 25, 1876, Custer’s 7th Cavalry advance party of General Alfred Howe Terry’s column attacked Cheyenne and Lakota tribes at their camp on the Little Big Horn River. The U.S. army did not realize how large the camp was. More than 2,000 Native Americans had left their reservations to follow Sitting Bull. Inspired by a vision of Sitting Bull’s, in which he saw U.S. soldiers being killed as they entered the tribe’s camp, the Cheyenne and Lakota fought back. Custer's badly outnumbered troops lost ground quickly and were forced to retreat. The tribes led a counter-attack against the soldiers on a nearby ridge, ultimately annihilating most of them.

The Native Americans' victory celebrations were short-lived. Public shock and outrage at Custer's death and defeat, and the government's knowledge about the remaining Sioux, led them to assign thousands more soldiers to the area. Over the next year, the new American military forces pursued the Lakota, forcing many of the Native Americans to surrender. Sitting Bull refused to surrender and in May 1877 led his band across the border into Saskatchewan, Canada. He remained in exile for many years near Wood Mountain, refusing a pardon and the chance to return.[16] In 1877, a year after the Battle of the Little Bighorn, Sitting Bull did his first interview on the subject. He said "they say I murdered Custer. It was a lie. He was a fool who rode to his death"

Surrender

Hunger and cold eventually forced Sitting Bull, his family, and nearly 200 other Sioux in his band to return to the United States and surrender on July 19, 1881. Sitting Bull had his young son Crow Foot surrender his rifle to the commanding officer of Fort Buford. He told the soldiers that he wished to regard them and the white race as friends. Two weeks later, Sitting Bull and his band were transferred to Fort Yates, the military post located adjacent to the Standing Rock Agency.

Arriving with 185 people, Sitting Bull and his band were kept separate from the other Hunkpapa gathered at the agency. Army officials were concerned that the famed chief would stir up trouble among the recently surrendered northern bands. Consequently, the military decided to transfer him and his band to Fort Randall, to be held as prisoners of war. Loaded onto a steamboat, Sitting Bull's band, now totaling 172 people, were sent down the Missouri River to Fort Randall. There they spent the next 20 months. They were allowed to return to the Standing Rock Agency in May 1883.

Wild West Show participation

In 1885, Sitting Bull was allowed to leave the reservation to join Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West show as a Show Indian. He earned about $50 a week for riding once around the arena, where he was a popular attraction. Although it is rumored that he often cursed his audiences in his native tongue during the show, some historians argue that he did not.[17] Historians have reported that Sitting Bull gave speeches about his desire for education for the young, and reconciling relations between the Sioux and whites.[18] Sitting Bull was reported to have cursed his audience in Lakota during an opening address celebrating the completion of the Northern Pacific Railway in 1884.[19]

Sitting Bull stayed with the show for only four months before returning home. During that time, he had become something of a celebrity and a romanticized warrior. He earned a small fortune by charging for his autograph and picture, although he often gave his money away to the homeless and beggars.[20] Sitting Bull realized that his enemies were not limited to the small military and settler communities he had encountered in his homelands, but were in fact numerous and possessed technological advancements. He also realized that the Sioux would be overwhelmed if they continued to fight.

Death and burial

Sitting Bull returned to the Standing Rock Agency in South Dakota after 4 months in Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show. In 1890 James McLaughlin, the U.S. Indian Agent at Fort Yates on Standing Rock Agency, feared that the Lakota leader was about to flee the reservation with the Ghost Dancers, so he ordered the police to arrest Sitting Bull.[21] On 14 December 1890, McLaughlin drafted a letter to Lt. Bullhead that included instructions and an outlined plan to capture the chief. The plan called for the attack to happen during dawn on December 15, and also advised the use of a light spring wagon to facilitate the chief's removal before his followers could rally. Lt. Bullhead decided, however, not to use the wagon. Instead, the police officers would force Sitting Bull to mount a horse as soon as the arrest was made.[22]

At around 5:30 a.m. on December 15, 1890, 39 police officers and 4 volunteers approached Sitting Bull's house. They surrounded the house, knocked and entered. Lt. Bullhead told Sitting Bull that he was under arrest and led him outside.[23] The camp awakened and men converged at the house of their chief. As Lt. Bullhead ordered Sitting Bull to mount a horse, he explained that the Indian affairs agent needed to see him and then he could return to his house. However, Sitting Bull refused to comply with orders and the police used force on him. The Sioux in the village were enraged. A Sioux man known as Catch-the-Bear shouldered his rifle and shot Lt. Bullhead who, in return, fired his revolver into the chest of Sitting Bull.[24] Another police officer, Red Tomahawk, shot Sitting Bull in the head and the chief dropped to the ground.

A terrible close-quarters fight erupted, and within minutes several men were dead. Six policemen were killed immediately and two more died shortly after the fight. Sitting Bull and seven of his supporters lay dead, along with two horses.[25]

Sitting Bull's body was taken to Fort Yates to be placed in a coffin (made by the Army carpenter[26]) and for burial. It is possible that in 1953 his remains were exhumed and reburied near Mobridge, South Dakota by Lakota family members who wanted his body to be nearer to his birthplace.[27] Some Sioux and historians dispute this claim and believe that any remains moved were not those of Sitting Bull.[28]

Legacy

Following Sitting Bull's death, his cabin on the Grand River was taken to Chicago to become part of the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition. The cabin was exhibited along with Native American dances.[29]

Sitting Bull was the subject of, or a featured character in, several Hollywood motion pictures:

- Sitting Bull: The Hostile Sioux Indian Chief (1914),

- Sitting Bull at the Spirit Lake Massacre (1927),

- Sitting Bull (1954),

- Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull's History Lesson (1976), and

- Into the West (2005)

- Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (2007).

As time passed, Sitting Bull became a symbol and archetype of Native American resistance movements.

- Legoland Billund, the first Legoland park, contains a Lego sculpture of Sitting Bull, the largest sculpture in the park.

- On September 14, 1989, the United States Postal Service released a Great Americans series 28¢ postage stamp featuring a likeness of Sitting Bull.[30]

- On March 6, 1996, Standing Rock College was renamed Sitting Bull College in his honor.

- Sitting Bull is featured as the leader for the Native American Civilization in the computer game Civilization IV.[31]

Sitting Bull College serves as an institution of higher education on Sitting Bull's home of Standing Rock in North Dakota and South Dakota. The name was changed from Standing Rock College to Sitting Bull College in 1996.

Gallery

|

Sitting Bull |

Sitting Bull's grave at Fort Yates, ca. 1906 |

Sitting Bull and Buffalo Bill, 1885 |

Sitting Bull in Pierre, South Dakota on his way to Standing Rock Agency from Fort Randall |

See also

- Black Elk

- Catherine Weldon

- Henry Mabb

Footnotes

- ↑ Encyclopedia Britannica. 20. 1955. p. 723.

- ↑ New Lakota Dictionary, 2008

- ↑ Utley 1993, p.66-72.

- ↑ Utley 1993, p.80.

- ↑ Utley 1993, p.82.

- ↑ Utley, Frontier Regulars 1973, p.242.

- ↑ Bailey 1979, p.84-5.

- ↑ Utley Frontier Regulars 1973, p.242.

- ↑ Utley Frontier Regulars 1973, p.244.

- ↑ Bailey 1979, p.106-7.

- ↑ Utley Frontier Regulars 1973, p.248.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Liberty, Dr. Margot. "Cheyenne Primacy: The Tribes' Perspective As Opposed To That Of The United States Army; A Possible Alternative To "The Great Sioux War Of 1876"". Friends of the Little Bighorn. http://www.friendslittlebighorn.com/cheyenneprimacy.htm. Retrieved 13 January 2008.

- ↑ Utley, Robert M. (1993). Sitting Bull: The Life and Times of an American Patriot. New York, New York: Henry Holt&Co.. p. 88, 122. ISBN 080508830X.

- ↑ Greene, Jerome (1993). Battles and Skirmishes of the Great Sioux War, 1876-77: The Military View. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. p. xvi, xvii. ISBN 0806125357.

- ↑ Greene, Jerome (1994). Lakota and Cheyenne: Indian Views of the Great Sioux War, 1876-1877. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. p. xv. ISBN 0806132450.

- ↑ Wood Mountain, Saskatchewan official site

- ↑ Utley 1993, p.263

- ↑ Standing Bear 1975, p.185

- ↑ Lazarus 1991, p.106

- ↑ Utley 1993, p.264

- ↑ Nichols, Roger L.; University of Oklahoma (2003). "American Indians in U.S. History". Norman Press. p. 160.

- ↑ Utley, Robert M. (2004). "The Last Days of the Sioux Nation, 2nd Edition". Yale University Press. p. 155,157.

- ↑ Utley, Robert M. (2004). "The Last Days of the Sioux Nation, 2nd Edition". Yale University Press. p. 158.

- ↑ Utley, Robert M. (2004). "The Last Days of the Sioux Nation, 2nd Edition". Yale University Press. p. 160.

- ↑ Dippie, Brian W. The Vanishing American: White Attitudes and U.S. Indian Policy. Middleton, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 1982.

- ↑ Snider, G.L., A Maker of Shavings, the life of Edward Forte, formerly 1st Sergeant, troop "D", 7th Cavalry 1936

- ↑ "Bones of Sitting Bull Go South From One Dakota to the Other.". Associated Press in New York Times. April 9, 1953. http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=FA0D15F63E55107B93CBA9178FD85F478585F9. Retrieved 2008-05-29. "A group of South Dakotans today lifted the bones of Sitting Bull, famed Sioux Indian medicine man, from the North Dakota burial ground in which they had been buried sixty-three years and reburied them across the state line in South Dakota near the Chief's boyhood home."

- ↑ "Restoring Dignity to Sitting Bull, Wherever He Is". New York Times. January 28, 2007. http://select.nytimes.com/2007/01/28/us/28thisland.html. Retrieved 2008-05-29. "Then, in 1953, some Chamber of Commerce types from the small South Dakota city of Mobridge executed a startling plan. With the blessing of a few of Sitting Bull’s descendants, they crossed into North Dakota after midnight and exhumed what they believed were Sitting Bull’s remains."

- ↑ Barker 1994, p.165.

- ↑ United States Postal Service, Postal History Web site

- ↑ Sid Meier's Civilization IV, IGN Entertainment, http://pc.ign.com/articles/654/654463p1.html

References

- Bailey, John W. Pacifying the Plains: General Alfred Terry and the Decline of the Sioux, 1866–1890. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1979.

- Barker, Barbara. "Imre Kiralfy's Patriotic Spectacles: "Columbus, and the Discovery of America" (1892–1893) and "America" (1893)." Dance Chronicle. Vol. 17, no. 2 (1994).

- Lazarus, Edward. Black Hills White Justice: The Sioux Nation versus the United States, 1775 to the Present. New York: HarperCollins, 1991.

- McLaughlin, James. Account of the Death of Sitting Bull and of the Circumstances Attending It. Philadelphia, 1891.

- Mooney, James. (Abridged version) The Ghost-Dance Religion and the Sioux Outbreak of 1890. Originally published as Part 2 of the Fourteenth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1892–93, Washington: GPO, 1896. Abridged version publication information: Edited by Anthony F. C. Wallace. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1965.

- "Sitting Bull Rises Again – Two Indians Deny Bones of Chief Were Taken to South Dakota." The New York Times. December 19, 1953.

- Prairie Public Radio. Dakota Datebook. September 3, 2004.

- United States Postal Service, Postal Service Listing of American Indian Stamps.

- Utley, Robert M. The Lance and the Shield: The Life and Times of Sitting Bull. 1st ed. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1993.

- Utley, Robert M. Frontier Regulars: The United States Army and the Indian, 1866–1891. New York: Macmillan Publishers, 1973.

- Standing Bear, Luther. (Reprint) My People the Sioux. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1975.

- Ullrich, Jan New Lakota Dictionary. Lakota Language Consortium, 2008.

Further reading

- Nelson, Paul D., 'A shady Pair' and an 'attempt on his life'- Sitting Bull and His 1884 visit to St. Paul, Ramsey County History Quarterly V38 #1, Ramsey County Historical Society, St Paul, MN, 2003.

- Adams, Alexander B. Sitting Bull: An Epic of the Plains. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1973.

- Brown, Dee. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1970.

- DeWall, Robb. The Saga of Sitting Bull's Bones: The Unusual Story Behind Sculptor Korczak Ziolkowski's Memorial to Chief Sitting Bull. Crazy Horse, S.D.: Korczak's Heritage, 1984.

- Greene, Jerome A., ed. Lakota and Cheyenne: Indian Views of the Great Sioux War, 1876–1877. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994.

- Manzione, Joseph. "I Am Looking to the North for My Life": Sitting Bull: 1876–1881. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1991.

- Newson, Thomas McLean. Thrilling scenes among the Indians, with a graphic description of Custer's last fight with Sitting Bull. Chicago: Belford, Clarke and Co., 1884.

- "Confirmation of the Disaster." The New York Times. July 7, 1876.

- "The Death of Sitting Bull." The New York Times. December 17, 1890.

- "The Last of Sitting Bull." The New York Times. December 16, 1890.

- Reno, Marcus Albert. The official record of a court of inquiry convened at Chicago, Illinois, January 13, 1879, by the President of the United States upon the request of Major Marcus A. Reno, 7th U.S. Cavalry, to investigate his conduct at the Battle of the Little Big Horn, June 25–26, 1876. (Reprint online) Pacific Palisades, Calif.: 1951.

- Sifakis, Stewart. Who's Who In The Civil War. New York: Facts on File Publishing, 1988.

- Urwin, Gregory. Custer Victorious: The Civil War Battles of General George Armstrong Custer. Lincoln, Neb.: Univ. of Nebraska Press, 1990.

- Utley, Robert M. The Last Days of the Sioux Nation. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1963.

- Yenne, Bill. "Sitting Bull." Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2008.

- Vestal, Stanley. Sitting Bull: Champion of the Sioux, a Biography. New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1932.

External links

- Sitting Bull's ledger drawings, Smithsonian Institution

- American Public Media Speaking of Faith interview of Ernie LaPointe entitled "Tatanaka Iyotake: Reimagining Sitting Bull"

- PBS The West article on Sitting Bull

- Friends of the Little Bighorn Battlefield article about Ernie LaPointe's efforts to move Sitting Bull's remains to the Little Bighorn Battlefield

- The Sitting Bull Monument Foundation in Mobridge, South Dakota

- "Sitting Bull: A Stone in My Heart", feature length documentary film on the life of Sitting Bull

- Sitting Bull at Find a Grave

- Historica’s Heritage Minute video docudrama about Sitting Bull. (Adobe Flash Player)

"Sitting Bull". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

"Sitting Bull". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||